By Ding Jo-Ann | 10 January 2011

If, as the saying goes, “History is written by the victors”, then the history of the Perak takeover would probably go like this: The three independents (not frogs) genuinely lost faith in their parties and conscience dictated that they become BN allies. The Sultan rightly decided that Menteri Besar Datuk Seri Mohammad Nizar Jamaluddin had lost the confidence of the assembly’s majority. He was also empowered under the Perak constitution to “deem” the Menteri Besar (MB) seat vacant when Nizar did not resign as instructed and appoint Datuk Seri Zambry Abd Kadir to fill it. Disputes surrounding the hasty dispatching of Nizar and equally hasty appointment of Zambry were fairly decided by an impartial court in accordance with the rule of law.

Najib, with Nasaruddin (behind), Osman (red tie), Jamaluddin (striped tie) and Hee (front)

Sultan went beyond constitution

In a series of “scholarly, satirical, whimsical, or polemical” articles, the authors set out why, in their view, something very rotten happened in Perak. Most criticised was the court’s affirmation that loss of confidence in the legislative assembly could be determined by the Sultan, taking into account “extraneous sources”.

Sultan Azlan Shah (source: sultan.perak.gov.my)

Constitutional expert Professor Andrew Harding was concerned about the long-term effects of such a decision. He agreed with the High Court decision, which was later overturned, that the state legislature should have decided whether Nizar had lost its confidence, not the Sultan. “Any other view,” said Harding, “not only renders the legislature otiose, but also opens the door to further constitutional crises arising out of behind-doors deals and manipulation [...].”

Other experts concurred. Singaporean constitutional professor Kevin YL Tan also said the Sultan had no power to dismiss Nizar or to request his resignation. Retired Court of Appeal judge Datuk NH Chan was of the same view, saying the Sultan was a constitutional monarch with no power to make the determination that he did.

Shad Saleem

Tarnished judiciary

Other than the monarchy, the judiciary’s reputation also suffered. “The judiciary has not come out of the Perak crisis well,” wrote Shad Saleem. “When the case first reached the courts, a judicial commissioner gave judgments that defy understanding…It left a bad feeling and did no service to a hallowed institution whose resurgence we were all praying for.”

Sivakumar is half pushed, half pulled out of the chambers. He was forcibly removed from the speaker's chair (Pic courtesy of Sinar Harian)

And then there was the extreme haste in which Zambry’s applications were processed in the Court of Appeal. “None of us have ever heard of an application being filed, sealed, issued and fixed for hearing before a [Court of Appeal] judge in less than 2½ hours,” said Amer Hamzah, referring to Zambry’s application to stay the High Court judgment declaring Nizar the rightful Perak MB. By contrast, Nizar’s application to set aside the stay order, was only heard eight days after it was filed.

“There were disproportionate delays in hearing Nizar’s application but great speed in attending to Zambry’s plaints,” said Shad Saleem.

Lasting impact

The Perak constitutional crisis will continue to have an impact, however some may choose to remember it. Prior to this, Malaysians may have long-believed that the monarchy played a largely ceremonial role in politics, bound tightly by constitutional limitations and convention. The BN’s quest to reclaim Perak and the court’s affirmation of the Sultan’s decision, however, have changed that equation. It has brought us into uncharted waters where the monarch, instead of elected representatives, can be directly involved in making crucial decisions — even decisions that could bring down a popularly elected state government.

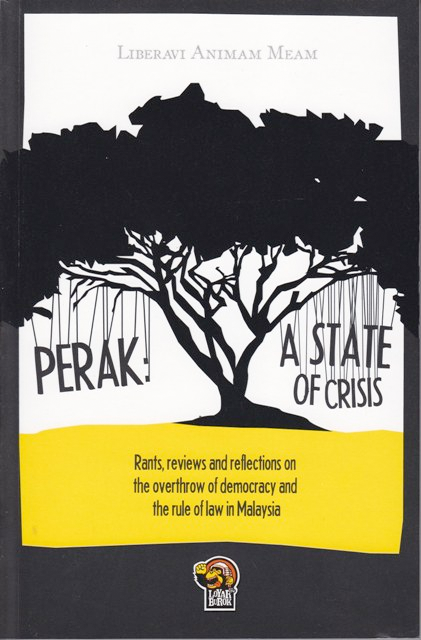

Perak: A State of Crisis

Some say Malaysians are generally a forgetful lot. Not helping is the fact that the approved history texts of events which shaped the nation are often lopsided. Despite the intense anger shown at the time of the Perak crisis, it is still doubtful what the results of the next state election in Perak will be. LoyarBurok hopes that in publishing this book, they are doing their part in helping Perakians and other Malaysians remember.

No comments:

Post a Comment